The ancient parish church of Monkstown today lies in ruins in the middle of Carrickbrennan Churchyard, surrounded by leaning headstones dating back to 1750. The church was built in 1668 by Edward Corker, using stones from an earlier church on the same site – a pre-Reformation stone church, known as the Chapel of Karibrenan (or Carrickbrennan) ot the church of Mochonna, which had been despoiled during the Cromwellian period.

As the local population grew, the church was enlarged with a new north-south aisle in 1748. By the 1780s, it had become too small for the congregation and a decision was made to build a new, larger church on a different site (the present one, at the centre of Monkstown village).

Monkstown, although still a rural seaside parish, was by now one of the most important, and also one of the wealthiest, parishes in Dublin. On Sundays, ‘great numbers of people’ would drive out of the city in their carriages to attend Monkstown Church.

In 1785, work began on the new parish church, on the Dublin to Dun Laoghaire road (the present site); it was consecrated on Sunday, 30 August 1789. It was a plain rectangular church, surrounded by open fields sloping down to the sea. Described as ‘the fairest country church in Ireland’, it could seat 340 people and was the only Church of Ireland church between Ringsend and Bray, apart from Stillorgan, further inland.

17 churches were all built in the ten years between 1824 and 1834. All were very much to the same blueprint – except Monkstown. It was the largest, most elaborate and most expensive of all, combining many of the features used in other church designs but on a much grander scale, resulting in this unique architectural “extravaganza”.

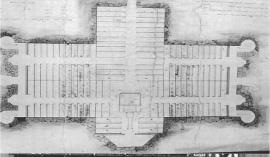

Semple’s 1831 church was a spectacular modification of the earlier 1789 Georgan church. Semple knocked down the east end and added two huge transepts onto the existing west end, to finish up with a T-shaped building. He built galleries 20 feet deep in each transept, in addition to the organ gallery already at the west end and a shallow extension and ‘vestiary’ at the east end. All the seating faced inwards towards the huge central wood ‘three-decker’ pulpit. The original west end of the Georgian church is preserved inside Semple’s church, up to the point where the north and south transepts begin.

However, the building of Monkstown Church did not run smoothly: a disastrous series of setbacks meant that it took an incredible eight years before the eventual opening. The site and design changes at least seven times, four different Building Committees were appointed, the builders went on strike when the money dried up, plans were lost, there were difficulties in raising money due to apathetic parishioners, personalities clashed and, to cap it all, Archbishop Magee, who had masterminded the whole project, lost the wife he adored, was crippled by a series of strokes and died before seeing the church completed. Semple’s church opened on Christmas Day, 1831 to mixed reactions.

Today, Monkstown Church is widely admired. Sir John Betjeman wrote in the 1958 Monkstown Review that Semple’s work ‘now seems bold, modern, vast and original … I think that Semple’s idea was to provide a striking general skyline and an arresting termination to the roads that lead to his church.

It was to be a cheerful Irish castle with a seaside rather than a fortress flavor. Why I like one building and not another I cannot always say. But in a life spent looking at buildings, the bold turrets so suited in their mouldings and terminations to the beautiful granite of which they are constructed, the plain walls with their deeply splayed window openings and the solid-looking base of the whole building make Monkstown Church one of my first favorites for its originality of detail and proportion…Only today is the original genius of Semple beginning to be appreciated’.

However, the reaction of Victorian Dublin was very different. A writer in The Dublin Penny Journal (12 July 1834) declared that he had never seen ‘a greater perversion of judgment and taste’ and that ‘there (was) not a spot in the church where the eye (could) rest without pain’. A parishioner wrote in Saunders’s Newsletter (30 September 1857) that ‘To anyone even slightly acquainted with the principles of church architecture, (Monkstown Church) cannot but appear simply hideous’, while the Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette (20 March 1880) thought that the church was not ‘suitable for a Christian place of worship’.

Many of Dublin’s well-known architects lived in Monkstown Parish and carried out work on the church at various times. John McCurdy, architect of the Shelbourne Hotel (1865) and the Marine Hotel in Dun Laoghaire (1869), built a chancel onto the east end in 1862. This was refurbished with a reredos and stone arcading at the east end in 1883 by Thomas Drew and William Mitchell. Drew lived at ‘Gortnadrew’ on Alma Road and was described in his obituary as ‘the most distinguished of living Irish architects’. Among other buildings, he designed the Ulster Bank, College Green; Trinity College Graduates’ Memorial Building (GMB); the Law Library at the Four Courts; Rathmines Town Hall; and St Anne’s Cathedral, Belfast.

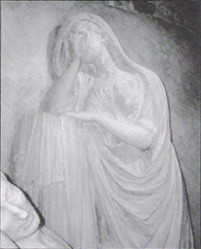

Richard Brown’s monument in Monkstown (left) and Nathaniel Sneyd’s monument in the crypt of Christ Church Cathedral (right), were both sculpted by Thomas Kirk. He used similar designs, as can be seen in the two grievings ladies. (Photographs by Arthur Ogilive and the author respectively)

Richard Brown’s monument in Monkstown (left) and Nathaniel Sneyd’s monument in the crypt of Christ Church Cathedral (right), were both sculpted by Thomas Kirk. He used similar designs, as can be seen in the two grievings ladies. (Photographs by Arthur Ogilive and the author respectively)

There are over 50 wall monuments in Monkstown Church. A writer in the Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette (20 March 1880) thought this was de trop, expostulating, ‘We have seen many churches, churches dating centuries back, but we never saw any with the walls studded over to an equal extent with those sad memorials of the departed worthies of the place’.

Three of these monuments, including the memorial to Richard Brown, were sculpted by Thomas Kirk (1777-1845), who also fashioned, in 1809, the 13-foot-high-stone of Admiral Nelson on top of the Pillar, blown up by the IRA in 1966. The grieving lady on Brown’s monument is almost identical to that on Nathaniel Sneyd’s monument in the crypt of Christ Church Cathedral, which kirk had sculpted several years earlier.

When I wrote my book on the history of Monkstown Parish Church, the only person I criticized was Sir John Lees – after all, he died in 1810, nearly 200 years ago. I knew that the last rector of Monkstown was a direct descendant – the remarkable late Canon Billy Wynne, founder of the Samaritans in the south of Ireland. But I was unaware of any other relatives.

This package was followed, shortly afterwards, by a rather heated e-mail from direct descendant of Lees, who lives on the west coast of America. When I gave this illustrated lecture to the Blackrock Society, yet another direct descendant travelled from England especially to attend and made herself known to me.

However, only a month after publication, a package arrived in the post from a direct descendant of lees now living in Kansas, in whose dining room hangs a portrait of John Armit, a nephew of Sir John and one of the principal benefactors of Monkstown Church. The artist Gilbert Charles Stuart had painted the portraits of both Armit and Sir John.

None of these three relatives, who each possesses a considerable amount of new material about the Lees family, were then known to each other. Because of my book, they are now in touch. This was one of the tangible pleasures of completing the project – it had taken nine long years and a mammoth chunk out of my life, and I thought, rather regretfully, that it was all over. However, I have reaped a steady trickle of new information since publication – evidence that the writing of a book is not the end, but merely the beginning of the next chapter.

A major fund-raising programme to finance essential restoration work on Monkstown Church was launched in November 2004 by the Most Rev. John R.W Neill, Archbishop of Dublin. The total cost over the next five years is estimated at 4.1 million euro.

Author Reference, Doctor Etain Murphy.